- The Hot Startups

- Posts

- Cafe Coffee Day: The Rise, Fall, and Remarkable Comeback of India's Largest Coffee Chain

Cafe Coffee Day: The Rise, Fall, and Remarkable Comeback of India's Largest Coffee Chain

How Malavika Hegde Slashed ₹7,000 Crore Debt and Revived CCD After V.G. Siddhartha's Tragic Death

In 1996, when coffee in India was mostly sold by Nescafé, V.G. Siddhartha opened the first Cafe Coffee Day on Bangalore's Brigade Road.

Within two decades, it grew into India's largest coffee chain with over 1,700 outlets.

Tragically, in July 2019, he walked onto a bridge in Mangalore and never came back. The letter he left behind mentioned unbearable pressure, mounting debt, and tax harassment.

This is the story of how India's first-mover in café culture created a category, captured the imagination of an entire generation, and then watched it crumble under the weight of aggressive expansion and financial misjudgment.

More importantly, it's about the woman who picked up the pieces - his wife Malavika Hegde - and mounted one of corporate India's most remarkable turnarounds, slashing debt from Rs 7,000 crore to Rs 465 crore.

CCD is executing one of the most brutal, unsexy, and fascinating turnaround strategies in modern Indian business history. Under Malavika’s leadership, CCD is undergoing ruthless prioritization required to save the business.

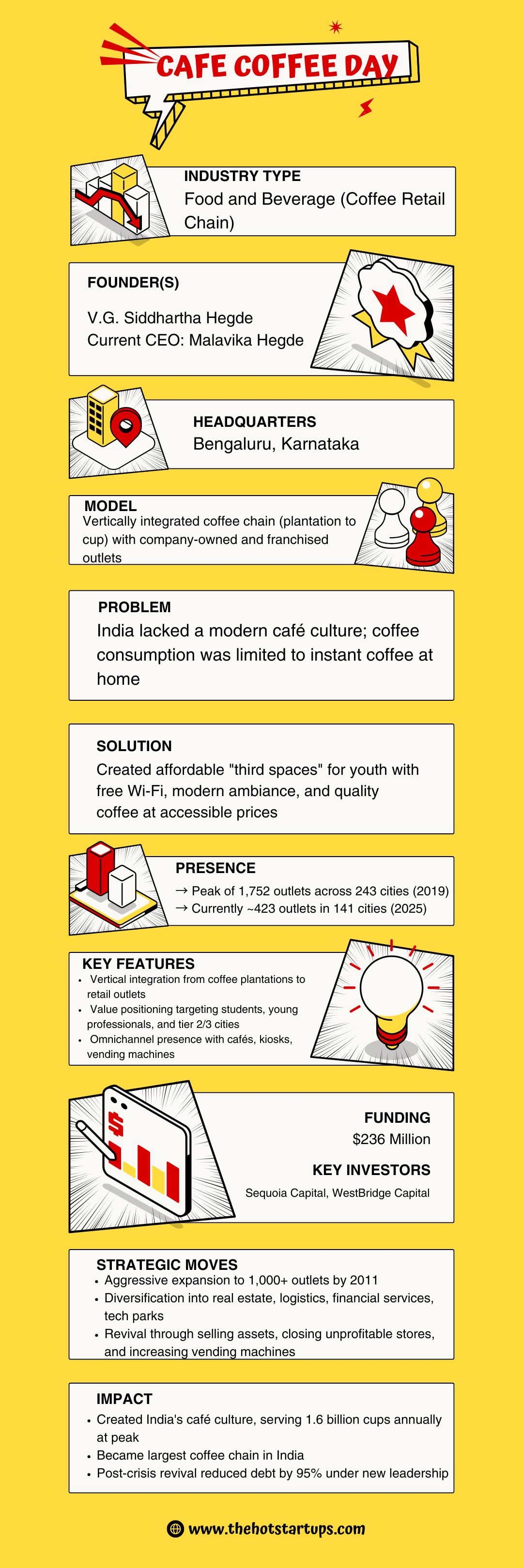

Here’s everything you need to know about CCD at a glance:

Let’s look at their start-up journey!

Some of our recent stories:

Sharks formed a cartel against this newcomer?

(How Recode Studios is profitable when Sugar Cosmetics is not)Can you challenge Colgate?

(Perfora says YES)K L Rahul and Katrin Kaif’s bet on wellness

(HyugaLife’s startup journey of building consumer trust)

The Strategy behind Building India's Coffee Empire

Outside India, cafés functioned as social infrastructure - not just places to grab coffee, but destinations where people met, worked, and built relationships. India had no equivalent.

CCD emerged with the slogan "A lot can happen over coffee" - capturing an innate aspiration of young, urban India.

First-mover advantage can be about being first to solve a problem people didn't know they had. Siddhartha created an entirely new category: the café as a social destination.

Vertical Integration as Moat

Siddhartha's background in coffee plantations gave CCD a unique competitive structure. The company owned 20,000 acres of coffee estates, making it Asia's largest producer of Arabica beans. It controlled curing facilities with 75,000-tonne capacity, roasting operations, and even manufactured its own espresso machines and furniture. This farm-to-cup vertical integration meant CCD had cost advantages and unparalleled quality control.

Coffee was procured at cost from owned estates. Distribution was through a hub-and-spoke model optimized for Indian logistics.

But vertical integration is a double-edged sword. It requires massive capital expenditure across multiple businesses. When coffee prices fluctuated or retail margins compressed, losses multiplied across the entire value chain. What looked like a moat during growth became an anchor during the crisis.

The Location Play

Following Tier 1 success, CCD opened in tier 2 and tier 3 cities where no competitor dared venture till then.

Moreover, they pioneered highway outlets, designed to appeal to young people, making long drives bearable with air-conditioned rest stops.

It was a part of the “CCD Value Express” to cater to the need for quick, quality, and affordable refreshments in malls and workplaces as well.

By 2019, it reached 1,752 outlets across 243 cities, far outpacing its competitors.

The consumer insight was brilliant: India's middle class wanted to feel sophisticated without breaking their budget. CCD delivered aspiration at an affordable price point.

The Growth Trap

The 2010 funding round led by KKR brought in $200 million. The company went public in 2015.

But growth metrics masked unit-level problems. Many new outlets weren't generating sufficient footfall to break even. Operational expenses - rent, salaries, inventory - remained fixed while revenues fluctuated. The company-owned-company-operated (COCO) model meant CCD bore all the risk.

Worse, CCD diversified aggressively into non-core businesses: Global Village Tech Park (real estate), Sical Logistics, Coffee Day Natural Resources, and financial services through Way2Wealth Securities. These ventures required continuous capital infusions.

By 2019, Coffee Day Enterprises had accumulated debt of Rs 6,547 crores.

In September 2017, income tax raids uncovered Rs 650 crore in alleged concealed income. Legal battles multiplied. Lenders grew anxious. To repay debt, he sold his 20.41% stake in Mindtree to L&T for Rs 2,858 crore post-tax. It wasn't enough.

The Competition: When Giants and Insurgents Converge

CCD created the playbook, but competitors wrote better chapters.

Starbucks entered India in 2012 through a joint venture with Tata Group, bringing global brand equity and premium positioning.

By 2023, Starbucks crossed Rs 1,000 crore in revenue.

They targeted affluent consumers willing to pay for the "Starbucks experience" - sleek interiors, customizable drinks, mobile app integration.

While CCD had 4x more stores, Starbucks generated comparable revenues with better margins.

Blue Tokai Coffee Roasters, founded in 2013, emphasizes single-origin beans, freshly roasted within four weeks of order, and direct relationships with farmers.

With nearly 133 stores and Rs 325 crore annual revenue in FY25, they captured coffee connoisseurs who found Starbucks too corporate and CCD too basic. Celebrity backing from Deepika Padukone and investors like A91 Partners gave them cultural cachet.

Third Wave Coffee, founded in 2016, explicitly targeted Starbucks. The interiors mimicked Starbucks' modern aesthetics while pricing remained slightly lower. Revenue soared from Rs 32 crore in FY22 to Rs 241 crore in FY24 - 67% growth. It demonstrated that specialty coffee was the new mainstream.

The Indian coffee market grew with increased out-of-home consumption, especially by urban youth, and premium shifts, but CCD's share eroded. The market Siddhartha created was now being dominated by better-capitalized, more agile competitors.

First-movers get punished twice: they bear the cost of customer education, then watch competitors leverage that education without paying the tuition. CCD taught India to drink coffee outside home. Starbucks taught them to pay a premium for it. Third Wave taught them craft matters. Each wave eroded CCD's positioning.

Strategic real estate became a battlefield. Starbucks began including lease clauses preventing Third Wave and Blue Tokai from operating on the same floor. The fight was for both protecting footfall and the prime locations left vacant by CCD's retreat.

CCD’s current retail offering is too expensive to be a daily habit for the masses but not premium enough to compete for the experiential dollar. Their outlets often feel dated, a nostalgic echo rather than a current contender.

Without a clear brand proposition, the retail arm remains the most vulnerable part of their ecosystem. The challenge now isn't expansion; it's defining what value those remaining 400 stores offer in 2026.

The Stumble: Debt, Death, and Disintegration

The pressures Siddhartha faced were both structural and personal. Structurally, CCD was bleeding cash from underperforming outlets. Personally, he had guaranteed company debt, meaning lenders could pursue his family's assets. The tax department's attachment of his shares blocked potential equity sales to Coca-Cola and Blackstone - deals that might have provided liquidity.

In the letter purportedly written before his death, Siddhartha mentioned failing to create a profitable business model despite his best efforts. He wrote about harassment from tax authorities and unbearable pressure from private equity investors demanding exits.

His death triggered a crisis of confidence. Stock prices plunged from Rs 193 to Rs 122. Employees feared job losses. Customers questioned whether their favorite café chain would survive.

What nobody anticipated was Malavika Hegde.

The Revival: From Grief to Governance

Malavika Hegde had served as a non-executive board member at CDEL but never in operations. When she took over as CEO in December 2020, she inherited Rs 7,000 crore in debt, plummeting revenues, and a brand associated with tragedy.

Her approach was counterintuitive. Instead of hiring expensive consultants or pursuing aggressive restructuring led by bankers, she went personal. In a letter to employees, she wrote that the CCD story was "worth preserving" and committed to bringing debt to manageable levels without sacrificing the brand's soul.

Malavika sold Global Village Tech Park to Blackstone. She liquidated non-core investments.

Rather than trying to save every outlet, she closed loss-making stores while expanding vending machines steadily.

This shift is profound from a business model perspective. A café is a heavy CAPEX, high OPEX bet requiring staff, prime real estate, and constant maintenance. A vending machine is an asset-light, recurring revenue engine with minimal overhead, generating cash flow with every push of a button, immune to the fickle trends of high-street retail.

Crisis leadership is about resisting panic. Malavika could have raised prices, fired everyone, or sold to the highest bidder. Instead, she made boring decisions: close bad stores, keep good ones, pay down debt, preserve brand equity. Boring wins.

Can CCD Reclaim Its Crown?

As of September 2025, CCD operates 423 cafés and 55,733 vending machines. While they aren't entirely out of the woods, they are no longer drowning. It proves that sometimes the best way to save a company is to shrink it. Malavika's next moves will determine whether CCD becomes a comeback story or a footnote.

Building a category is hard. Defending it is harder. Reviving it after near-death is the hardest. Café Coffee Day did all three.

CCD's trajectory reveals the precise mechanics of how first-mover advantage erodes, how vertical integration can become a liability disguised as an asset, and why the metrics you chase during growth can destroy you during consolidation.

The story of Cafe Coffee Day is often told as a tragedy, but that does a disservice to the current management's resilience. It is a brutal, necessary case study in corporate survival. They proved that a legacy brand doesn't have to die when its original product-market fit expires.

Accepting a smaller, less glamorous reality has allowed CCD to keep the lights on. The days of being India's cultural coffee icon are behind it, yet as an actual business, CCD stands on firmer ground than it has in ten years.

Key Insights:

First-Mover Reality

Being early builds the market, but unless you create strong moats, followers will benefit more than you.Vertical Integration Risk

Owning the full supply chain magnifies profits in good times and losses when margins shrink.Misleading Growth Metrics

Store count and revenue hide weak unit economics; sustainable businesses are built on profitable outlets.Debt Diversification Trap

Expanding into adjacent businesses with debt increases risk unless your core business reliably generates surplus cash.Brand Over Short-Term

Protecting brand trust during crises ensures long-term survival, even if short-term gains are sacrificed.

Reply